Augustus John's first wife came to accept his affair with Dorelia. Apparently she said "men must play and women must weep". Her photo does not to me reflect accetpance to me.. She looks dead in the eyes or was that the photography process, the long sitting? Am I just projecting my insecurity onto her thoughts? Or is she displaying the weeping she talks of, the pain in my heart surely shows in my eyes. Can I learnt o accept that every man I know and have known is not content with one woman?

M is related to him somehow and I'm jelaous of that. Her art connections and celebrity status. Isn't that silly. It makes me yet again a nobody yet again comapred to a somebody, through connection to a real somebody.

I would like to move away from such jealousy and insted be comfortable being the person I am. I don't like the seeming arrogance that seeps through when people are claiming their somebody status through such connections. Some people name drop all the time. It's irritting but also expresses some sense of a lacking in self and a need for importance as a result. Even if it's secondhand. This is ego. And even more irrituating are those people wo are fooled by status. I can be on of them displayed through my very jealousy. Ugh so complex being human. So much work involved in seeing it ll for what it is and trying to get back to the reality of the moment,

Augustus John was an iportant artist of england in the early 1900's. An amazing draughtsman so they say. An artisit skilled in detailed drawings. I like his portraits.

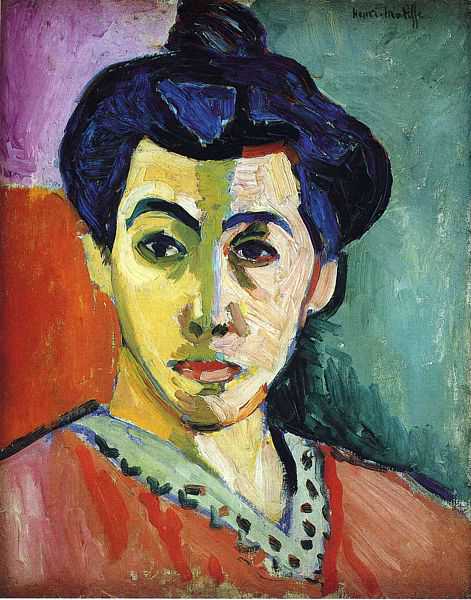

Influenced by Innes, a man who seems to have used influences from imprssion to pre-empt the arrival of the post impressionists. And Innes was in turn enthused by Matisse and fauvism. John and Innes were not convinced that art was not a vehicle for good draughtsmanship. I think I can see the ways in which moving out of conventional reproduction feels more creative. I can see what I see and maybe even attempt at copying it. Technically this is a talent I suppose. But to convey creative ideas using art as the vehicle. Now this is another matter all together.

Influenced by fauvism is suddenly a way to reflect what the feelings are not simply what's being seen. Some people do not like this I suppose, they want to be awed, is that a word?, by like-ism. I made that up. But I want to create what I feel. And sometimes I don't know how to put it into words. I can see feeling though in like-isms too.

In fact was Munch influenced by Fauvism? His paintings often seem to reflect feelings rather than like-ism. I remember the fallen tree painted in yellow specifically. I liked it for its perspective and colour but only when someone else had pointed that out to me.

Innes and John spent time in Wales - drinking. JOhn was a ealthy celebrity in the prime of his life befireding Innes completely unknown and much younger. Despie this John painted him with a "cadaverous cast of features". What a lovely turn of phrase from the BBC4 documentary which inspired me. Hence writing this information gleaned from it.

John called Innes an intellectual virgin. Innes had a direct connection with the landscape. And John picked out qualities in his portraits.

Perhaps they paved the way deviating from constraints of British rigidity.

Augustus had many lovers; Euphemia Lamb, social butterfly. Eccentric and an adventurous spirit, she irresistibly beautiful. She wasn't an exclusive sort and Innes became more impotant in her life. It wasn't believed John and Innes were rivals in this affair. It reminds me of being in a relationship with CO when married to DM. They both knew. I think there was rivalry with CO but DM was too lapsidasical and probably more concerned with being free to drink and gamble. Perhaps he was just less possessive. I think so. If only that could have remained but I was still too needy and wanting conventionl I think. It was painful but intriguing and fun all at the same time. What an adventure of a life I've had. If only I wasn't so insecure.

She resembles J I think. I was jealous of J's looks. Something qite stunning about her. If she didn;t go into her fairy tale romaticism. That just wasn't for me. How judgemental. Well I was, I found it irritating but that doesn't mean it was wrong. I don't make a judgement in that way. We were destined to move on from each other. I am still sad about that though.

John lived with the gypsy's. Doing what he deamed of as a child. I dream of travelling. Places less touched by westerners. Exploring and keeping moving. Yet I crave security too. I wonder if I can have faith in the freedom.

JOhn said "certainly I have an interest in women ... in beauty. If it's beauty it's love, in my case"

He also said " as an artist you've got to get excited about something before you can do anything and beauty is an excitant".

Now that's interesting. I get intrigued and that is an inspiratoin to do something. But curiosity ad an attraction to things that glitter can also be a danger. I think they can create the desire for more. Recongise the addictive cycle starting. It only excitment is the motivator then it's out of balance. There's a need for self discipline otherwise other things that matter get left to drift away. Beauty can be blurred or fade in the cold light of reality.

Painting all fairly cursory he paints bushes and sheeps as dashes and dots.

His scenery was secondary to his portraits but encompassed in the same painting. I wonder if he had an affair with Tabullah?

Innes contracted tuberculosis and was dying. His relationship with Eupemia was dying at the same time.

He kept on painting until he could paint no more. John outlived Innes by a further 46 years. JD Innes was 27 when he died. Living a life of recless dissipation, drinking too much. He died without a fading reputation just very young. John continued to fly the Welsh flag. He abandoned landscapes and instead was a ortrait painter for the stars. He said he had a "fishy reputation as a painter because I'm out of date". Innes was his inspiration. When working together they almost created a school of their own. They were not in cometition but brought together different strengths. They were in harmony with their different talents. I wonder if was actually like that.

Rebecca John says she prefers INnes' interpretations more decorative and more fantastical and more appealing paintings. Not so real compared with John's like-isms.

Intresting. She had said earlier that she wished she had known a younger not so grumpy grandfather. I wonder if there is some histoiry of resentment or if she really does prefer Innes' work.

An article in an old Guardian. I wish I'd been intersted at that time to get to the exhibition. And recently I missed an exhibition in Chichester. Pity.

He was the bewitching bohemian to her secretive introvert; he the toast of the art world and she the talented recluse. But as the Tate's forthcoming retrospective reveals, the paintings of brother and sister Augustus and Gwen John are opposites which attract. By Tim Adams

Exactly 100 years ago, in the summer of 1904, there was, it would be fair to say, a good deal going on in the lives of the brilliant young Welsh artists Gwen John and her brother Augustus.

The pair - he, loud and passionate; she, spirited and self-contained, two years his elder - had grown up together famously unruly on the beaches and cliffs of Pembrokeshire. They lost their mother early in their childhood and, to escape the attentions of maiden aunts, had educated themselves in nature, peered over the shoulders of weekend artists to observe 'the mystery of painting', and learnt portraiture by sketching each other obsessively.

Both won places at the Slade School of Fine Art in London, where Augustus, in particular, had been hailed as a draughtsman of genius. They had then, at the turn of the century, drifted into a life of easy bohemianism in the capital, sharing friends and houses, painting portraits and establishing themselves at the heart of the avant-garde. After the summer of 1904, however, their lives, and their art, began to diverge in extreme ways.

It had begun the previous year when, at a gallery opening in Holborn, Augustus had met a young art student called Dorelia McNeill. Augustus, then 25, was already married to a fellow student from the Slade, Ida Nettleship. They had one son, and another on the way. From the moment he saw Dorelia, however, he fell hopelessly in love. He persuaded her to pose for him as a model, went out with his wife and sister to choose exotic clothes for her to wear while he sketched her, and began the relationship in which she became his muse, his lover and his obsession.

Gwen, perhaps fearing where her brother's affair might lead, persuaded Dorelia to accompany her on a 'walk to Rome', which would have the effect of easing some of the tensions at home, and would allow her, too, to paint the bewitching model. The pair had set off by boat to Bordeaux and followed the Garonne to Toulouse, sleeping on the river bank, trading portraits for food, pursued all the while by Augustus's letters, pleading with them to return to London. Eventually, in the spring of 1904, Gwen and Dorelia abandoned their original trip and went to Paris.

As a younger girl, Gwen had described herself as 'shy as a sheep', but now, at 27, she felt 'amorous and proud'. In this spirit, and looking for work, she went to knock on the door of Auguste Rodin, the most famous artist in the city, to offer herself as a model. By the end of the summer of 1904, Gwen was posing for the sculptor every week. She had also fallen into a love affair with him that was to define much of the remainder of her life. Rodin was 63 and in letters of the autumn Gwen would describe to him how she was the 'happiest woman in the world' and how 'all my days are so delicious when I pose in the mornings and it's sunny and I know you [Rodin] are coming later'.

Augustus, meanwhile, who was already becoming known as the outstanding young artist in London, had by September 1904 persuaded Dorelia back to London. In part, this was spurred by his wife Ida, who wrote to Dorelia offering her 'wonderful concubinage'. The three of them, along with Ida and Augustus's two sons, then established the infamous consensual household they had imagined. Augustus had waited for Dorelia impatiently as she adventured with his sister, and he now took to drawing and painting her obsessively. In his letters to her while she was in France, he had complained that, 'You sit in the nude for these devilish foreign people, but you do not want to sit for me when I asked you.' This was a problem quickly rectified. Later that year, Dorelia became pregnant by Augustus and ,the following summer, had her first child, the wonderfully named Pyramus, while in a caravan on Dartmoor.

Back in Paris, Gwen, besotted with Rodin, was busy reinventing herself, perhaps in order to please her mentor, as a more rigorous, less carefree woman. With his encouragement she devoted herself to her painting, and began to develop the bleached palette that came to characterise her work. She remained frustrated in her desire to become Rodin's wife, however, and, when he died in 1917, her artistic habits became entrenched in grief, and in her newfound Catholic faith. She became reclusive in a village outside the city, painting the same scenes over and over again: self-portraits and interiors, a series of studies of the nuns at her local convent, pictures of solitary cats and of a convalescent neighbour. She developed her own unique method of painting, mixing chalk and plaster with her oils, building up fragile layers which lent her work its almost supernatural stillness.

Augustus, meanwhile, found him-self surrounded by an ever-increasing brood of children and an ever-expanding band of society admirers. He dressed with flamboyance in purple silk shirts and gypsy earrings and big hats; he painted travellers and learnt Romany, spending a lot of time in the south of France, visiting Picasso in his studio and sharing his home with his wife and lover and their children. After the death of Ida, in childbirth with their fifth son in 1907, Augustus lived with Dorelia, who continued to be his idealised model, as well as mother to his seven sons and two daughters. (Other children and more clandestine mothers emerged only later, to leave the final count of Augustus's offspring at 13.)

Though they never wholly forgot their early familial bond, Augustus and Gwen thus became more singular and detached from one another as the years passed. After the First World War, they were living very different lives, and painting very different pictures. For some of these reasons, it is now nearly 80 years since they have shared an exhibition space, which had been a habit of their early years. That fact, however, will change next month when Tate Britain puts brother and sister back together in a major retrospective.

The staging of the new show, which aims to cast fresh light on the shared inspiration and contrasting characters of the two artists, was in part the idea of the biographer Michael Holroyd, whose book on Augustus first exposed the detail of the painter's crowded romantic life. When Tate Modern and Tate Britain divided, Holroyd saw there might be a chance to reappraise Gwen and Augustus's work, and wrote to Tate director Sir Nicholas Serota to suggest it.

In a perverse way you could see this as a payment of dues. Holroyd's book, published in 1974, and revised in 1996, seemed effectively to shut down critical interest in Augustus's work: the dramatic life of the artist came wholly to overshadow the painting, completing a process that had begun in his lifetime. Augustus was subsequently written out of many art histories of the 20th century, while Gwen's reputation, as she was claimed by feminist writers, only grew.

Holroyd believes that the ebb and flow of their fortunes was in part a backlash against the imbalance of the notice they received while alive. Augustus, the archetypal artist-bohemian, was a national monument, never out of the papers and, according to one critic in 1914, 'the most famous artist in the world'. His sister, despite a strong critical reception, was virtually unknown. 'After both their deaths there was a feeling that Augustus had had all the attention while his sister had had none,' Holroyd suggests. 'That by the sheer force of his personality he had made her invisible. The many subsequent books about her have tended to make her a victim. This perception was actually a little false to the lives they both had, but it stuck.'

Augustus himself had started to feel the beginning of this trend after Gwen's death in 1939. In a letter of 1952, he wrote to correct an essay by a friend on the work of his sister: 'With our common contempt for sentimentality, Gwen and I were not opposites,' he insisted, 'but much the same really, but we took a different attitude. I am rarely exuberant. She was always so; latterly in a tragic way ... She was never "unnoticed" by those who had access to her.'

Despite these protestations, the caricature became fixed. In part, Augustus John's reputation was a casualty of his longevity. He continued to paint up until his death in 1961, by which time he was beached as a Romantic portrait painter in a world of resolute abstraction. Holroyd believes - 'strictly as an academic historian, obviously' - that Augustus lived too long, perhaps even 40 years too long. Had he died after the portrait of Thomas Hardy [1924], or even after that of Dylan Thomas [1936] 'he would have died with a reputation that would only have grown when we imagined what he would have gone on to achieve. He was above all a youthful lyrical artist,' Holroyd says, 'and that attitude does not age well.'

Oddly, given he was such a man of action, it was the Great War that undermined Augustus John as a painter. It seems to have left him unsure. In the years leading up to the war he was a creator of effortless figures in landscapes on small wooden panels, flooded with light and colour. At the time, his paintings were criticised for lacking drama, or a story, or for being just groups of static figures in space. 'In fact those paintings were about the absence of anecdote,' Holroyd suggests, and in this sense were ahead of their time. 'But style no longer seem-ed relevant to him after the war. And then he became a portrait painter, and quite a hit-or-miss one, at that.'

Gwen's career was the reverse. She felt her way toward her mature style, which offered something like the opposite of sensation. You could easily walk past her paintings, but once you looked they drew you in. They were similar to Augustus's in one respect, however: she also avoided story. 'Her paintings have the feeling of life being in the past,' Holroyd says. 'While his are all about possibility. He is before the action, before the curtain comes up, she is afterwards, once the theatre has emptied.'

When Holroyd began to work on his biography, he was fortunate to discover an ally in Dorelia, still alive in her eighties and living at the home she had shared with Augustus, Fryern Court at Fordingbridge. She persuaded his far-flung children - legitimate and otherwise - to co-operate. Still, Holroyd says, keeping all sides of the family on board was a major enterprise. 'That was the book that did most to increase my diplomatic skills.'

The current keepers of the flames of Augustus and Gwen are their grandchildren. The Tate exhibition has been shaped in part by Rebecca John, daughter of Caspar John - the late First Admiral of the Fleet - and granddaughter of Augustus and Ida. Now in her fifties, Rebecca lives in a top-floor flat in Covent Garden, and is herself an exquisite watercolourist.

One of the things she hopes the show will do is debunk the myth that there was great rivalry between the siblings. 'Augustus always felt protective toward Gwen,' she says. 'He gave her money. He introduced her to John Quinn, the great American collector, who supported her work. Augustus was a very generous man.'

She believes the exhibition will provide powerful evidence of their particular gifts. 'He outshines her completely as a draughtsman. Her drawing is extremely tentative. As in life, he just jumped straight in and did it with wonderful stark slashes of line. They were opposites in every way. He lived on the wing, and worked outdoors a lot of the time. She painted these extraordinary empty interiors. Their very Christian names seemed to set the agenda: Gwen is Welsh for white, the absence of colour. Augustus evokes gold.'

Her grandfather was 'very maddened', Rebecca believes, by the fact that Gwen bequeathed all her work to Edwin, his third son. Gwen had seen a lot of Edwin in Paris in her later life. He had been a boxer and she disapproved; she persuaded him to make an unusual career change and become a watercolourist.

In later life Edwin became very protective of Gwen's legacy. His daughter, Sara, who now lives in the Black Mountains, recalls how her father kept all Gwen's work 'very close to his heart. Augustus and my father discussed things and clouds would form over Fryern Court. They both fought over whether a book should be written about Gwen, that there should be exhibitions,' Sara says. Her father resisted much of that. As it was, the silence and mystery about Gwen, Rebecca believes, worked in her favour. 'When, on the death of Edwin, the estate was taken over by the dealer Anthony d'Offay,' she says, 'he knew just how to bring Gwen to a new audience. And the feminists swooped. It was such a beautiful scenario. Here she was, the quiet sister of this monstrous male ego who lived with two women and who had numerous children, taking herself off to Paris and living this secretive artistic life.'

Rebecca remembers her grandfather well in old age and is not convinced of that judgment. 'As a young man,' she says, showing me some photographs of Augustus wading in a river in his twenties, 'he was incredibly handsome, devastating. And he had a powerful effect on every woman who met him. They wanted him. But in retrospect he gets the blame, of course. One ridiculous story came from Caitlin Thomas [wife of Dylan] about being raped by him. Caitlin Thomas was a well-known bitch and fantasist.'

In a sense, Rebecca John believes that her grandfather has been a victim of the taste for obscurity in art. 'My own theory is that art today has to be incomprehensible. So Augustus is far too straightforward. You can't intellectualise with Augustus. He hated intellectuals. The fact is with him you have a beautiful figure, or a perfect line, or wonderful colour and that's it. I hear it about Augustus: "Oh he could draw as well as anyone in the world, but so what?"'

Champions of Gwen's work, by contrast, such as critic Lisa Tickner, see her painting as coming 'as close as perhaps an image can do to picturing consciousness'. No one has cracked the code of her colour and art historians love that repressed mystery. 'She was so profoundly deliberate,' Rebecca says. 'Augustus was anything but deliberate. He dashed things off, he had no attention span.'

All the grandchildren I speak to recall the trepidation they had at sitting for their grandfather as models. Anna John, daughter of Augustus's first son, David, remembers her summers at Fryern Court well. 'We would go down there for the holidays. He did not dandle us on his knee. He would sit at the far end of the table and we were supposed to entertain him so, of course, we used to fight to sit as far away as possible. I sat for him as a model a few times. He stamped and smoked and grunted all the while, paced about and insisted that you kept still. It was rather terrifying. Dodo [Dorelia] used to send one of us down to get him from his studio in the garden for lunchtime and you would knock on the door with great alarm at disturbing him from his work, and he would let out this tremendous shout.'

Rebecca recalls her grandfather's look. 'Everyone felt his glare. He was very deaf at the end of his life, so it was difficult to have a conversation with him. My father always used to say that by the time they got on, Augustus was so deaf that everything had to be shouted at him. He used to like the grandchildren to talk to him, though, but mostly that required too much courage for me. The only time I did pluck up the courage was when he asked me a booming question. One time it must have been about school, because all I can remember is that I said I was learning Latin. And he was rather impressed with that.'

Dorelia's strength of personality matched that of Augustus. 'You would never forget her,' Rebecca says. 'His drawings give you the wrong impression. She was not dreamy and limp-wristed. A lot of the figure drawings are very pre-Raphaelite, an attempt to idealise her. I knew her in old age, but I do not think she had changed dramatically. She was short in conversation, quite snappy, very down-to-earth, and she had a lovely little low giggle. Very, very alive.'

Sara John puts this more succinctly: 'She was absolutely wonderful,' she says, of one of the great artistic muses of the 20th century. 'But she wasn't a granny to knit you a pair of socks.'

Growing up, the grandchildren knew only the sketchiest outline of their grandparents' colourful past. 'Until Michael Holroyd wrote the biography, we did not know anything really,' Rebecca says. 'The book changed the life of the family. We had to read it to discover our history.'

The aspect of their legacy they did know about, though, was Augustus's once-great artistic reputation. Many of numerous grandchildren went to art college, but all laboured under the name they had inherited. Anna John, who subsequently married cartoonist John Glashan, went to St Martin's to do fine art, but: 'bearing this name for five years. Augustus was in the papers all the time. The bohemian lifestyle, as well as the work. Though it felt natural for me to draw, it was all rather impossible.' It has taken Rebecca, too, nearly all her life to realise the talent she feels she inherited. 'I studied jewellery design,' she says, 'but I was always happier with paper and pencil than blowtorch and metal. I liked the fine detail of leaves and shells, so I loved to draw, but I had a problem and that was my grandfather. In our family it was not considered wise to draw.'

Putting Gwen and Augustus together, she believes, is a 'bold' move on the part of the Tate. Curator David Fraser Jenkins has addressed this by concentrating on what the siblings had in common: what he describes as their shared 'outsiderliness' and a mutual need to escape. Holroyd likes to think of the show as an opportunity to look down both ends of a telescope at once: Augustus intent on making things larger than life, Gwen concentrating and distancing. Both painters seemed to have realised much the same thing. Augustus wrote of his sister in 1942 as the 'greatest woman artist of her age, or, as I think, of any other'. He predicted that 'In 50 years' time I will be known as the brother of Gwen John.' That his prophecy has all but come true, and that it would be his own reputation that was now seen in need of repair would perhaps have amused him. He would, in any case, after all these years, have enjoyed the prospect of equal billing.

· Gwen and Augustus John is at Tate Britain, London, from 29 September 2004 to 9 January 2005; Augustus John, Masterworks from Private Collections 1900-1920, Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert Gallery, 38 Bury Street, London SW1 (020 7839 7600) from 29 September to 29 October